Axiom 38-The Undiscovered Country explores this topic. I hope you'll take a look!

|

I've recently been asked to participate in three interviews about my new book, which touched on questions such as "What is your vision for higher education in the arts?'

Axiom 38-The Undiscovered Country explores this topic. I hope you'll take a look! Higher Education by Design: Best Practices for Curricular Planning and Instruction has been published!

Please visit the Routledge site: www.routledge.com/Higher-Education-by-Design-Best-Practices-for-Curricular-Planning-and/Mackh/p/book/9780815354185 Economics is the study of infinite wants and finite means, the study of constrained choices. This is true for individuals and governments, families and nations. Thomas Sowell said it best: no solutions, only tradeoffs. To get the most out of life, to think like an economist, you have to be know what you're giving up in order to get something else. That's all opportunity cost is: what you have to give up to get something.

~ Russell Roberts[i] To get what we want, we must also give something up. It’s basic to the human experience – we cannot “have it all” 100% of the time. (It’s also the source of the curious idiom, “you can’t have your cake and eat it, too,” because if we eat the cake, we don’t have it anymore.) The economic term for this is “opportunity cost”: the tradeoffs that must be made in order to achieve a goal or obtain something we want. This concept is among the core principles of both economics and academic leadership. Often, opportunity cost is a simple exchange of money for a product or service. We don’t usually think much about the impact of small transactions like filling the car’s gas tank, but every decision we make is accompanied by a set of related options we did not select and the impacts of these choices within a web of interdependent factors. Academic leaders must be constantly aware of this principle, because each decision, large or small, will have multiple consequences. For instance, if we want to add a new course, someone needs to teach it. If it will be taught by a current faculty member, then another faculty member will have to shoulder the responsibility for one of the courses that the professor who is assigned to the new course taught previously. If the new course requires hiring a new faculty member because no one in the department possesses the necessary expertise, the cost of that professor’s wages will have to be included in a budget. However, budgets are finite, so any increase usually requires a corresponding decrease in another area. Where will the money come from? Furthermore, bringing a new person into an organization will also have non-monetary impacts such as potentially changing the interpersonal dynamics of the department. All of these factors and more are inseparable from the decision to add a new course to the schedule. Opportunity cost is not limited to monetary factors, just as fiscal responsibility is but one aspect of our job as academic administrators. It extends to every aspect of the organization and the people within it, from our oversight of faculty development, to our interactions with community members, to the vision we cast for the organization – it encompasses all of the strategic trade-offs we make each day, often without even being consciously aware of their impact. Therefore, learning how to manage the complex and varied opportunity costs of academic leadership requires the application of four key strategies: prioritization, strategic planning, pragmatism, and resourcefulness. Prioritization begins by accepting two realities. First, we cannot meet each of our responsibilities optimally each and every day. If we’re focusing on completing Task A, then Task B (and C and D) will remain un-done. The key is to ensure that our attention shifts from day to day, not spending too much time on one thing at the expense of another. If, today, we choose to address a faculty concern, then tomorrow we deal with the analysis of recent trends in enrollment. The day after that, we focus on meetings with new faculty members. Of course each day will be filled with multiple activities and we must give our attention to more than one task, but it’s exceptionally difficult to continuously devote 100% to every area all of the time. Prioritization forces us to determine where it’s most advantageous to focus our energies, and maintaining a logical rotation of priorities helps ensure that each one receives attention in due course. This brings us to reality two: we cannot do everything alone. When it’s not possible to devote the personal time or attention a problem will require, we must find someone who can carry that responsibility on our behalf. Administrators need a core group of trusted individuals who work collaboratively to advance the organization’s mission and vision. Prioritization is crucial here as well. Some tasks should remain the provenance of the leader, such as any time we’re called upon to be the face and voice of our organization, when we need to interface with upper administration, or in matters where we must exercise the authority of our position to achieve a goal. Other tasks can and should be handled by other people whom we trust. We have to apply our best judgment to the decision of whether to complete a task ourselves or trust another individual to take care of it, just as we determine the sequence in which tasks will be accomplished. Some priorities demand our immediate attention, while others are less pressing. Knowing what to do, when to do it, and by whom it must be done is crucial to organizational success. Conversely, thinking that we can do everything alone and all at once is a recipe for disaster. Planning and prioritization ensure accountability and prevents lesser responsibilities from falling through the cracks or being subsumed by more pressing matters. An academic strategic plan is the outcome of our prioritization efforts. It formalizes who’s responsible for achieving different priorities, clarifies roles, and establishes benchmarks for accomplishment and schedules for when different tasks must be done. A sound strategic plan removes doubt and confusion, replacing them with clarity and shared purpose. Strategic planning should occur at a minimum of two levels. First, a long-range plan maps out where the organization should be five or more years into the future, setting challenging goals that inspire collective effort. Second, it should also encompass short-term goals with step-by-step measures for their achievement, defined by attainable objectives and concrete benchmarks providing evidence of progress. Next, we must approach leadership pragmatically. Both vision and idealism are necessary to our forward momentum, but because every decision an administrator makes has a cost, we must temper our outlook with practicality. This includes accepting that our choices will spark resistance. No innovation, no evolution, no growth occurs without opposition. The members of our organizations tend to prefer the status quo and some will vociferously object to any proposed change, even when the situation is dire. Accepting this fact and handling it pragmatically allows us to both anticipate the negativity that we are going to encounter and also to learn from those in opposition to us. Critics serve an important function in pointing out the deficiencies in our plans, giving us the opportunity for revision and refinement. We will probably not be able to change the minds of those determined to cling to the status quo or to resist change, but our challenge is not to earn their endorsement – it’s to reach a point where the organization we lead is better than when we began. Pragmatism allows us to make a clear-eyed assessment of a situation, to anticipate likely outcomes and challenges, and plan a course of action that allows us to navigate the maze successfully. Finally, resourcefulness allows us to work within institutional structures but not to be constrained by them. Perhaps no human institution is as tradition-bound, complicated, or difficult to change as higher education, yet leaders need not be confined by its apparent inflexibility. Applying an entrepreneurial mindset to the challenges we face allows us to find a path through what at first appears to be an impenetrable forest of obstacles. Even as we accept the economic reality that to gain we must be willing to lose, we should remain adamantly unwilling to settle for defeat until all possibilities have been exhausted. An entrepreneurial mindset seeks opportunity, fueled by vision but facilitated by a spirit of resourcefulness. Where can we find the resources we need among those that already exist within the institution? Can we re-purpose, revise, transform, or utilize existing resources differently? Can we identify community or corporate partners who might help us reach our goals? Most importantly, resourcefulness is about finding opportunities that we can build upon to improve the organization we lead. Institutional legacies, histories, or traditions – “But this is the way it’s always been done!” - prevent us from perceiving these prospects. Resourcefulness helps us to find a way around this obstacle, allowing us to consider situations from a fresh perspective and to envision new ways to meet the challenges we face. The principles of economics don’t apply to higher education because of its high cost or financial complexity. They apply because higher education is a human institution and therefore follows economic patterns that have been observed, analyzed, and applied for generations. Recognizing and applying these to our practice of leadership allows us to identify strategies that will foster to the greatest success for our organizations. Therefore, prioritization, strategic planning, pragmatism, and resourcefulness empower us to engage in continuous improvement of both the institutions we lead and our own expertise as academic administrators. AXIOM: To maximize their organization’s success, academic leaders should remain aware of the opportunity cost of their decisions, engaging all available approaches and assets and taking a pragmatic stance that incudes strategic planning and prioritization along with resourceful identification of opportunity. [i] Roberts, Russell (Feb. 5, 2007). Getting the Most Out of Life: The Concept of Opportunity Cost. Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2007/Robertsopportunitycost.html Additional Reading Taylor, T. (March 15, 2013). How Successful Leaders Prioritize – Examining the Steps to Successful Tasking. Dale Carnegie Training. http://www.dalecarnegiewaynj.com/2012/03/15/how-leaders-prioritize-examining-the-steps-to-successful-tasking/ Strategic Planning in Higher Education: A Guide for Leaders. Center for Organizational Development and Leadership. http://oira.cortland.edu/webpage/planningandassessmentresources/basicassessmentresources/RutgersPlanning.pdf Gunelius, S. (April 15, 2010). Are You a Pragmatic or Idealist Leader? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/work-in-progress/2010/04/15/are-you-a-pragmatic-or-idealist-leader/#532db0e83e67 Baldoni, J. (January 13, 2010). The Importance of Resourcefulness. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/01/leaders-can-learn-to-make-do-a McCadden, S. (January 10, 2011). Shared Responsibility: Advantages of Creating a Team of Leaders. Remodeling. http://www.remodeling.hw.net/business/operations/shared-responsibility-advantages-of-creating-a-team-of-leaders I just posted Axiom 33 - Mind the Gap, but the formatting doesn't transfer well to the blog area. Please click HERE to read it.

“You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great – and that's what being a spacefaring civilization is all about,” Musk has said. “It's about believing in the future and thinking that the future will be better than the past. And I can't think of anything more exciting than going out there and being among the stars.”[1]

"Crazy things can come true," Musk said. "I didn't really think this would work — when I see the rocket lift up, I see a thousand things that could not work, and it's amazing when they do.". . . "I've seen rockets blow up so many different ways, so it's a big relief for when it actually works," he added.[2] On February 6, 2018, SpaceX successfully launched its first Falcon Heavy rocket, an unprecedented feat in the history of space exploration that not only sent a Tesla roadster into orbit around the sun and Mars; it landed two of the rocket’s three reusable boosters back on Earth intact. SpaceX’s achievement was no overnight wonder, however. Founder Elon Musk first announced the Falcon Heavy project in 2011, predicting launch by 2013, yet five more years of testing, innovation, development, and experimentation were needed to achieve this goal.[3] Of course, a large and complex team finally made the launch possible, but the true rocket fuel driving the entire SpaceX enterprise emanates from SpaceX founder Elon Musk himself, through his powerful vision of making humanity into a spacefaring civilization. Vision is more than just a compelling idea about the future – it’s the very heart of leadership. Vision is the source of a leader’s energy, the spark that ignites a flame in others, and the sustaining fire that powers the entire organization towards achieving its goals. A leader’s most important responsibility is to formulate a vision for the organization and to cast that vision so compellingly that it instills the leader’s passion in others’ hearts as well. Without vision, an organization ceases to achieve forward momentum. Without the vision of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the US might still be a British colony. Without President John F. Kennedy’s vision of manned spaceflight, Neil Armstrong may never have stepped foot on the Moon. Or would we have made as much progress in space exploration without the creative visions of the future cast by Jules Verne, Gene Roddenberry, or George Lucas? Even on a smaller scale, cellular telephones were directly inspired by communication technologies in Roddenberry’s StarTrek, and Elon Musk named the Falcon rocket project for the Millennium Falcon in Lucas’s StarWars. Dreams can and do become reality. Vision alone, however, is impotent without subsequent action. Furthermore, a vision nearly always requires a dedicated team to bring it to life, radiating out through concentric circles of stakeholders who partake in a shared idea of what the future could be. How does the process begin? Visions sometimes strike like a bolt from the blue, but they might also dawn slowly, built on a leader’s years of gathered experiences and observations. Conversely, vision might depend on a leader’s deliberate act of will, engaging in a thorough and thoughtful analysis of present conditions and considering what will be necessary to lead the organization into a better future. Regardless of how the vision emerges, it remains only an intellectual idea unless it’s harnessed to passion. Leaders cannot just think their visions are worthwhile – they must believe in the vision to the core of their being. Visions should be so strong, so compelling, that leaders would gladly pursue them without support; they must be so committed to a vision that they embody it, unhesitatingly working towards the vision’s achievement with their own hands. Former President Jimmy Carter didn’t just serve as a spokesman for Habitat for Humanity: he put on his old clothes and swung a hammer alongside the other workers.[4] George Washington could have spent the winter of 1777-78 in the comfort of Philadelphia, but he chose to stay with his troops at Valley Forge, sharing in their hardships and using the bleak winter to train them for the challenges to come.[5] This kind of participatory, self-sacrificing leadership is more inspiring than any pep talk. Others see this commitment and cannot help but be moved. But unless the leader is 110% passionate about the vision and personally invested in its achievement, nobody else will be inspired to act. The leader’s passion and action combine to form the lynchpin upon which the successful achievement of the entire vision depends. Once recognized, the vision must be shared, but casting this vision across the organization as a whole should occur in three stages. First, the leader should gather support by meeting individually with members of his or her core leadership team to share the vision as a private conversation between colleagues. The more such meetings can occur the better, igniting the imaginations of the core group’s members and building a strong base of support. The next step is to bring those individuals together, discussing the vision and working in concert to craft a vision-casting presentation for the entire organization. The team helps to anticipate and work through potential problems, providing valuable insights that the leader might not have considered. Sharing the vision among the members of the core group multiplies everyone’s passion, fostering the ownership and commitment that will be essential for implementing the vision. The team must also clarify and crystalize the vision into a short, inspirational, memorable statement. In The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization (2011), management expert Peter Drucker said that an effective statement should be “short and sharply focused. It should fit on a T-shirt. . . . It must be clear, and it must inspire. Every board member, volunteer, and staff person should be able to see the [statement] and say, ‘Yes. This is something I want to be remembered for.’”[6] A vision statement should immediately communicate why action is imperative, whereas mission statements tell how the organization will achieve its purpose. Vision statements are less comprehensive than mission statements but more inspirational, and they might be specific to a particular initiative or project rather than attempting to encapsulate the organization’s overall purpose for existence. A crystalized vision statement also provides focus and prevents distractions by allowing the organization to differentiate between actions that support the vision and those that do not. The last stage in casting the vision is to persuasively present it to all of the organization’s stakeholders. Timing is important, with natural starting points of the organization’s year tending to be most advantageous. In higher education, this usually happens at the beginning of the fall semester when everyone is preparing for the new academic year, and a second opportunity for a fresh start occurs in January after the semester break. It’s very important that the leader personally deliver the vision-casting message, convincingly communicating his or her passion for the vision. Nevertheless, vision-casting events cannot rely only on a prepared speech, no matter how heartfelt. Incorporating creative elements designed to accentuate the emotional content of the message such as multimedia presentations, storytelling, music, and drama draws upon the power of the arts to reach beyond the audience’s intellect, stirring their hearts to truly catch the spark of the vision. An effective vision-casting presentation will amplify passion far beyond the leader’s original vision, producing joy, energy, determination, and ownership. The audience should respond with enthusiastic affirmation – “Yes!” “This is why I’m part of this organization!” “This is what I’ve dedicated my life to achieve!” It’s the rocket fuel that propels the organization into the future. Once the vision has spread across the organization, the leader must direct this newfound energy towards achievement. Implementation of a vision demands a different set of skills than vision-casting, but the process occurs in similar stages, beginning, again, with the core leadership team. Collaborative strategic planning catalyzes energy into accomplishment. The team must work in concert to transform the abstract ideas of the vision into concrete action steps with measurable and achievable goals. Vision statements only address the key question of “Why?” but the team will need to identify answers to many other questions as well. Where are we now? Where do we want to be? What will we need to do in order to get there? How can we divide the work into manageable steps? Who will take responsibility for making each step happen? The team might also need to revisit the organization’s mission statement and previous goals to ensure that every effort contributes to the actualization of the vision. The strategic plan should establish measurable and achievable long-term goals, broken down into short-term targets. As the team leaders work with the organization’s members to implement the vision, the leader’s role changes from vision-caster to vision-sustainer. Vision naturally diminishes and grows cold across the organization without regular infusions of the leader’s passion and energy, just as a bonfire needs fresh logs to keep it burning. It is the leader’s duty to sustain the flame, in one-on-one interactions, team meetings, and occasional gatherings of the entire organization’s membership. The team members who have accepted responsibility for leading implementation of the action steps should collect data as the process moves forward. Progress fuels continued momentum, and celebrating the achievement of each action step also helps to keep the organization’s energy level high. Furthermore, the leader must discern where forward momentum is lagging or where individual commitment has faded, determining how best to apply motivation to address the problem. This stage of leadership requires application of the leader’s management skills, pressing on towards the goal with relentless resolve even when decisions might be painful or difficult. Action steps sometimes fail, and projects often reach dead ends. We often have to pick ourselves up and start over again. Elon Musk said he’d seen rockets blow up in a thousand different ways, which was why he was so overjoyed at the success of the Falcon Heavy launch. Part of leadership is to endure many failures along the way, sustaining the vision even in the face of repeated setbacks. Diligence, commitment, dedication, and unflagging resolve are all essential to visionary leadership, as is unflinching willingness to pitch in and work with one’s own hands. Leadership is messy and frustrating and disheartening sometimes. Even when we know our mission is urgent, even though our vision still compels us, we grow weary. We provide the fuel that sustains vision in those we lead, but how do we maintain our own energy? By remaining committed to the continual development of our leadership practices and potential. Finding a mentor, reading voraciously about leadership, and seeking the company of other leaders who can serve as a support system are just a few ways that we can continue to grow as leaders, refueling our passion for our work. Vision at its best takes on a life of its own. It endures beyond the leader who cast the vision, beyond the leadership team, and sometimes even beyond the organization itself. Space exploration outlasted both President John F. Kennedy and drastic cutbacks in NASA’s budget and operations, now taken up by visionaries like Elon Musk. The fight for civil rights continues to the present day, half a century after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Democracy has grown beyond the work of Adams and Jefferson and spread across the globe. In this same vein, no leader remains in his or her position forever. Perhaps the greatest legacy we can give the organizations we lead is a vision that carries the organization forward well into the future. The fire we ignited in the hearts of others has grown to a stable, sustaining flame, ensuring that our efforts will continue long after our own leadership has come to an end. This is truly the measure of success – to inspire, establish, and provide for the sustainability of something larger than ourselves. As academic administrators, we maintain a passion for our disciplines and for training young scholars to advance the borders of human knowledge beyond our classrooms. We deeply believe in facilitating our students’ success, equipping them with the knowledge, skills, and competencies they will need to achieve sustainable careers. We motivate our faculty to share in these dreams and to work with us towards their achievement, and we inspire our students to develop dreams of their own. Therefore, our ability to cast a vision is an important part of academic leadership, supported by the application of management techniques to sustain that vision. Furthermore, we not only need to fuel the passion of those we lead but must replenish our own passion through the continuous study of leadership. It’s a tall order, to be sure. Nevertheless, the visions we cast will endure beyond our time as deans, chairs, directors, provosts, or presidents. We strengthen the academic enterprise, but even more importantly our efforts make a lasting impact on our students. We touch thousands of lives over the course of our careers, both directly and indirectly through our faculty and staff. A vision for improving graduation rates, for example, is not a matter of mere statistics – the life of each student who graduates as the result of our efforts is demonstrably improved by the implementation of our vision. It’s easy to lose sight of the importance of what we do, to be preoccupied by our daily responsibilities. Keeping our eyes fixed on a compelling vision and allowing it to re-energize our passion for higher education might just be the most important thing we do as academic leaders. AXIOM: Vision is the heart of leadership but it must be coupled with concrete action by all members of the organization to bring that vision to life. [1] https://mashable.com/2018/02/05/spacex-launching-falcon-heavy-rocket/#7LG3jU2ccOqf [2] https://www.space.com/39618-elon-musk-falcon-heavy-spacex-reaction.html [3] https://www.space.com/39607-spacex-falcon-heavy-first-test-flight-launch.html [4] https://www.habitat.org/volunteer/build-events/carter-work-project [5] http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/valley-forge/ [6] Drucker, P. (2011). The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization. John Wiley & Sons. Education can be stifling, no question about it. One of the reasons is that education — and American education in particular, because of the standardization. . . does not emphasize diversity or individuality; it’s not about awakening the student, it’s about compliance; and it has a very linear view of life, which is simply not the case with life at all. ~Ken Robinson[1]

Our systems of higher education are built around a centuries-old legacy that has touched the lives of countless administrators, faculty, staff, and students. When this involves traditions such as covering a campus statue with red crepe paper before a big football game, or newly-engaged couples ringing the landmark tower’s bell seven times, it’s charming – serving a valuable purpose in building and maintaining community. Other legacies, however, are less beneficial. We unquestioningly accept “the way it’s always been done,” refusing to look beyond longstanding institutional practices that ought to be open to examination. As Sir Ken Robinson so ably pointed out, the systems still in place across all of American education developed during the industrial age,[2] designed to yield a consistent product – educated citizens. This has been true for so long, we don’t even recognize the obvious connection to manufacturing. Our colleges and universities are designed to ensure uniformity – each person who earns a certain degree will have received similar instruction, met the same requirements, and had a comparable educational experience. This means that a B.S. in Chemistry, for example, will be essentially the same no matter which institution grants the degree, notwithstanding the relative prestige or status of the institution. We even apply metrics that quantify and evaluate our work, much like the quality control practices in factories. However, no matter how consistent and reliable our educational methods may be at imparting a pre-determined set of knowledge, skills, and competencies, it does not mean that students who earn a degree are truly educated. Certainly, students progress through our systems, abiding by the stale rules that change with glacial slowness, but many never become fundamentally transformed by the education they received. They are merely recipients of a standardized credential. When someone who earns a living in higher education makes such a claim, it raises the specter of controversy, since those who contribute to such systems appear to be complicit in their perpetuation. Nevertheless, each person who works within the educational system can and should strive for improvement where opportunity exists or circumstances demand change. Every faculty member or academic administrator should support continuous improvement of our institutions and the expansion of our disciplines. We should resist the tendency to take the easier path that leads inexorably to the comfortable trap of legacies, rules, and traditions, guarding against our natural inclination to allow our longstanding institutional habits to limit the advancement and improvement of higher education. After all, progress occurs every day, even when our colleagues turn a blind eye to changes occurring beyond the campus gates. Furthermore students come to us expecting our best, believing that we are leaders in our disciplinary fields. Do our credentials uphold the trust students place in us? Do we actively maintain our disciplinary engagement? Or has our professional involvement been stalled by legacy or tradition? We should never lose sight of the fact that students quite literally mortgage their futures for the privilege of studying with us, incurring staggering debt to avail themselves of the opportunities that they presume we will provide. According to the College Board, the average cost of tuition, fees, room and board at a private college for the 2017-2018 academic year was $38,830, which translates to $151,320 for a four-year bachelor’s degree. An in-state student at a four-year public university could expect to pay $20,770 per year for tuition, fees, room and board, or $83,080 for a bachelor’s degree.[3] Unless we ourselves are the parents of college-age children, we seldom stop to count these costs, yet knowing the financial burden that our students place upon themselves (or that their parents incur through “Parent Plus” federal student loans) should give us pause. By way of comparison, $150,000 could buy a comfortable single family home in many areas of the country; and $83,000 is more than the cost of a brand-new Mercedes-AMG C63 S Coupe, or a Chevy Corvette Grand Sport, or a Jaguar F-Type R Dynamic.[4] Some faculty and administrators may bluster at this comparison, saying that we cannot measure the value of college education in mere dollars and cents. Nevertheless, we DO put a price tag on it, which means that we must also consider whether we are giving students their money’s worth. We in higher education must help one another perceive change and opportunity through a benefits-oriented lens. In other words, we must ask ourselves: does our choice to remain steeped in legacy, tradition, and manufacturing-era operational models draw us closer to the goal of preparing students to lead successful, sustainable lives after graduation? Or does it drive us further away? Academic maturity, leadership (and make no mistake: all educators are leaders), and scholarship each allow us to develop the ability to judge the constructiveness of our decisions, allowing us to recognize that high-quality scholarship has nothing in common with doing things the way they’ve “always been done.” We should never allow our intellectual curiosity to be sated, nor our eagerness for professional growth and achievement to wane. We cannot permit our departments, colleges, or schools to remain stagnant when the world all around us continues to evolve. If we do, our houses of learning become mere museums where we are but docents, introducing students to the treasured antiquities of our disciplines. Instead, we should each remain on the cutting edge of disciplinary achievement so that our students will be exposed to the most current information it is within our power to provide, empowering them to go forth from our institutions prepared for the ever-changing rigors and challenges of the professional world. Higher education can no longer adhere to a model of mass production, using the obsolete machinery that has been in service for many decades. We should recognize that each student deserves an individualized educational experience that will be personally transformative, not only delivering the tools to succeed now, but instilling a passion for lifelong learning, an insatiably curious mind, and a spirit of innovation that transcends the basic skills and competencies typical of standardized degree progressions. When we can truly say that we do this, then we can legitimately claim to be educators. AXIOM: Higher education must provide students with a transformative education that empowers them to transcend the skills and competencies of a given degree program. [1] Brown, Karen. (May 24, 2013). An Interview With Sir Ken Robinson. Etsy Journal. https://blog.etsy.com/en/sir-ken-robinson-on-creativity-and-finding-your-element/ [2] Robinson, K. (2010). Changing Education Paradigms. RSA Animate-TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_changing_education_paradigms [3] College Data, a service of 1st Financial Bank. “What’s the Price Tag for a College Education?” https://www.collegedata.com/cs/content/content_payarticle_tmpl.jhtml?articleId=10064 [4] Road and Track (June 27, 2017). The 15 Best Cars Under $100,000. http://www.roadandtrack.com/car-culture/g4277/the-13-best-cars-under-100000-dollars/?slide=2 “Silos build the wall in people’s minds and tie the knots in their hearts.” ~ Pearl Zhu[1]

It’s only natural for human beings to prefer the company of others like themselves. A study conducted by Northwestern University professor Lauren A. Rivera revealed that hiring process in the labor market rest not only on finding a qualified candidate for a position but someone who was culturally similar to the hiring manager.[2] Rivera’s findings support earlier research by scholars such as Kanter (1977) or Lazarsfeld and Merton (1954), who also found that cultural similarities were the basis of attraction and social stratification.[3] In higher education, “culture” is often defined by our academic disciplines, so it’s no surprise that scholars choose to associate with like-minded colleagues. We understand one another’s research and practice, and most importantly, we share a common passion for our disciplines. Close association between scholars in the same field of inquiry creates an environment in which teaching and learning in that field can grow and develop, striving to expand knowledge within the discipline and convey new discoveries to students. But this attractive familiarity can also become a barrier separating us from practitioners in other fields, resulting in disciplinary silos with their own value systems, insider language, and norms for scholarly inquiry and accomplishment. The more deeply steeped we become disciplinarily, the more difficult it can be to forge productive relationships with colleagues whose research, teaching methods, professional jargon, and habits of mind seem foreign to us. Rather than serving to enhance scholarly productivity and protect academic rigor, disciplinary silos slowly become little more than border walls, keeping insiders in and outsiders out, reinforced by longstanding habit. Make no mistake, the advancement of disciplinary knowledge is crucial to the mission of every institution of higher learning, as is the training of new practitioners. Nevertheless, the workplace outside of academia emphasizes teamwork and collaboration over monodisciplinary focus. Employers want to hire candidates who can communicate clearly and effectively, work well on teams, and solve problems creatively, not just those with particular disciplinary expertise.[4] Corporate professionals work on interdisciplinary teams, and some workplaces such as IDEO abandon the idea of professional disciplines altogether.[5] Outside of academia, no discipline exists in isolation, even though our institutional structures, histories, and traditions can make it seem so. The world’s problems are complex, requiring a systems thinking approach that examines the linkages and interactions between a problem’s interrelated components and parts. No single discipline can solve “wicked problems” like world hunger, poverty, crime, disease, or political unrest alone. Instead, we need to bring our finely-honed disciplinary expertise to bear on collaborative projects where each participant can make a meaningful contribution to something greater than a single discipline alone could achieve. Furthermore, interdisciplinarity strengthens both teaching and learning. Students learn more effectively when we help them to connect their disciplinary skills and knowledge to other contexts or applications. Because our disciplines don’t exist in a vacuum, it is incumbent upon us to show students how their learning will intersect with their other studies and their professional lives. This applies to all courses from general education requirements to senior seminars and graduate study. After all, why do we require all students to complete liberal arts requirements? Because they have value outside of the classroom, imparting a specific set of transferable competencies[6] that prepare students to communicate clearly, analyze and evaluate intelligently, think critically, and work collaboratively – the very qualities employers are seeking in our graduates. All disciplines have both intrinsic and instrumental value, but it is up to us as faculty and administrators to convey both of these identities to our students and help them build the connections they need in order to fully mobilize all of their learning after graduation, not just their specialized disciplinary achievement. So how do we break out of our silos? As with many other things in life, it is up to us to take the first step for ourselves. Find a partner in another field who is also interested in working on an interdisciplinary research project or co-teaching a course that incorporates both of your fields. Study successful instances of interdisciplinarity already occurring at your institution or elsewhere and investigate how you could apply similar strategies. Or conduct a little background research, like reading Surveying the Landscape: Arts Integration at Research Universities (2015),[7] which outlines a number of approaches to interdisciplinary research and teaching, along with examples of institutions where this has been especially successful. As important as it is to move beyond our silos, it’s still not easy. Colleges and universities often voice their support for interdisciplinarity, or establish centers and institutes that bring varied disciplines together, but longstanding systems and practices may stand in the way of their best intentions. When retention, promotion, or tenure rests only on individual disciplinary achievement, it’s difficult to invest significant professional energy into research or teaching that might impede career advancement. Certainly, we must continue to hone our skills within our disciplinary divisions, so admirably equipped for that purpose, and persist in our hard work to deepen disciplinary knowledge. But we must also carry our valuable expertise beyond the self-imposed walls of our silos, strengthening the linkages and intersections between our fields of expertise in order to truly achieve the ideal of a university - establishing a whole and cohesive body of knowledge far greater than the sum of its formerly siloed parts. In this way, the human body might serve as an effective metaphor, with each physical system representing a distinct entity that functions in concert with all others in order to sustain life. All are essential, and none can do the job of the others, yet they work together so that we can do all of the amazing things humans can do, from composing an aria to competing in a triathlon. Un-siloing our disciplines allows these productive interactions to occur unhindered by the structures and systems that have long kept us separated by custom, policy, or tradition. Institutions that establish greater flexibility in matters of retention, promotion, and tenure to allow for interdisciplinary work realize positive growth. Offering incentives to faculty who choose to pursue interdisciplinary research or teaching, or providing support systems for those who choose to venture in new directions beyond their prior comfort zone are also productive strategies. There are as many paths to success as there are faculty and administrators willing to boldly travel beyond their disciplinary borders, leaving the doors of the silo open in the ardent hope that others will follow. When we unlock our silos, we emulate most of the world outside our doors, where interdisciplinarity is the norm and disciplinary exclusivity the exception. This can only be of benefit to our students and our professions, not diluting our disciplinary rigor as some may fear, but infusing our disciplines with fresh ideas and new vitality, propelling us into a brighter future. AXIOM: Disciplinary structures and systems continue to serve a valuable purpose in higher education but they should also allow for interdisciplinary research and teaching beyond longstanding borders. [1] Zhu, Pearl. (2016). IT Innovation: Reinvent IT for the Digital Age. BookBaby. [2] Rivera, L. (2012). Hiring as Cultural Matching: The Case of Elite Professional Service Firms. American Sociological Review. 77(6) 999-1022. http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/journals/ASR/Dec12ASRFeature.pdf [3] Kanter, Rosabeth. 1977. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books; and Lazarsfeld, Paul and Robert Merton. 1954. “Friendship as a Social Process: A Substantive and Methodological Analysis.” Pp. 18–66 in Freedom and Control in Modern Society, edited by M. Berger, T. Abel, and C. Page. New York: Van Nostrand [4] Ryan, L. (March 2, 2016). 12 Qualities Employers Look for When Hiring. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lizryan/2016/03/02/12-qualities-employers-look-for-when-theyre-hiring/#77eaf2352c24 [5] Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design. Harper Collins. [6] Ireland, C. (June 6, 2013). Mapping the Future. Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2013/06/mapping-the-future/ [7] Mackh, B. (2015). Surveying the Landscape: Arts Integration at Research Universities. University of Michigan Press. Full text download available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015095766708;view=1up;seq=2 I've been working on a series of short writings about teaching and leadership in higher education that I've loosely titled "Axioms." This project is ongoing, with Axiom 28-The Challenge Coin completed today. You'll find the document below, and others on the Leadership page here on my site. If you have ideas for new Axioms, I'd love to hear them! Please post them in the comments below.

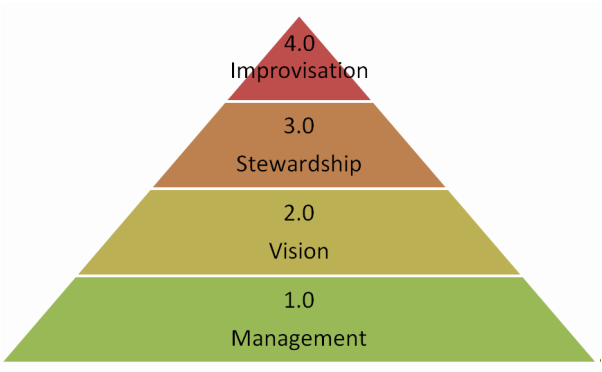

In the course of my professional activities, I enjoy the privilege of engaging with academic executives and administrators. In fact, I’ve interviewed 338 such individuals, including: 27 university presidents or vice presidents; 38 provosts, vice provosts, or associate provosts; 171 deans, associate deans, or assistant deans; and 102 directors, chairs, or department heads to date—an experience that has informed my understanding of the nature of academic administration. This led to the development of a theory of academic leadership: just as software receives periodic upgrades, we might consider educational leaders as achieving increasingly higher levels of skill and expertise. Leadership 1.0: Management At the most fundamental level, administrators cause people to do things. This often happens through the exertion of influence such as setting deadlines, offering performance incentives, or imposing consequences if a task is not completed. Accomplished managers do this with sensitivity and respect. The most skillful inspire their employees to high-level performance rather than resorting to force. Management requires the ability to maintain complex organizational structures. It is foundational to all academic leadership. Leadership 2.0: Vision Administrators at the next level move beyond management to employ the principles of constructive and positive leadership. They prefer to communicate a contagious vision, seeking to inspire employee performance through intrinsic motivation rather than the application of external incentives. This includes practicing genuine listening, exhibiting compassion, and demonstrating enthusiasm for the organization’s mission and goals. Inspirational leadership through communication of a shared vision produces a stronger workplace and fosters collaboration. Vision is essential to promoting or coping with change. Leadership 3.0: Stewardship Servant-leadership takes vision to the next level. Leaders support their employees by providing opportunities for success and recognition. They refrain from self-promotion, but place others in the forefront, facilitating their professional accomplishments and inspiring those employees to become more deeply engaged in working towards the organization’s success. Servant-leaders also consider the larger context of any situation, keeping an eye towards the impact of their decisions on their professional discipline; on their department, college or school; and on the institution as a whole. Leadership 4.0: Improvisation Educational leaders apply all of these skills on a daily basis, but the very best administrators move fluidly between them. Most institutions of higher education operate under a set of policies, procedures, rules and regulations. These place limits on what the administrator is able to do, but they also provide a structure within which appropriate action becomes clear. At the top level of administrative competency, leaders possess a firm grasp of these governing principles and systems. They are able to apply this knowledge with discernment and wisdom as they respond to challenges on all three levels, managing, inspiring, and supporting employees and students. The taxonomy represents the differing approaches to leadership in ascending order, but not as a hierarchy. Management is fundamental to leadership and is essential to sustaining organizations. Vision, stewardship, and improvisation all depend on a strong managerial foundation. Indeed, many organizations seldom move beyond this foundation, particularly those that remain unchanged for long periods. Differences in these levels of leadership become most apparent when problems arise. Level 1.0 administrators react authoritatively, often by issuing mandates and imposing consequences for non-compliance. Level 2.0 administrators respond by gathering their team together, employing discussion and reasoning and they lead employees in collaborative problem solving. Level 3.0 administrators seek out the employees best equipped to address the problem and empower them to achieve solutions. Each one of these strategies may be effective; however, taking a single approach rarely leads to the highest quality solution. The best administrators do all of these things, engaging in improvisation to fluidly adapt each strategy as necessary. They do not lose sight of the “big picture” even as they focus on the immediate need. They keep an eye on institutional requirements, the health of their department, and the wellbeing of all students and employees. They seek to resolve the situation without sacrificing educational quality. They maintain personal integrity and provide unflinching support for everyone under their leadership. They also accept responsibility and hold themselves accountable to upper administration. Level 4.0 leadership requires foresight, creativity, and intelligence. Even more, it demands the ability to see beyond what is to what is possible. Although the majority of daily administrative tasks exist on the level of management, Level 4.0 leaders approach even the most mundane administrative tasks with an understanding of how their actions will affect the organization as a whole and the individuals involved in the immediate situation. Vision and stewardship permeate everything they do, whether consciously or intuitively. Undoubtedly, both my background as a corporate executive and longstanding interest in the topic of leadership have shaped my views, along with my present research and professional service. A corporate CEO and a university president share many of the same concerns and characteristics: after all, whether an organization is primarily engaged in producing a tangible product, providing a necessary service, or educating students, every organization is comprised of human beings. Leadership is about the relationship between the leader, the persons led, and the organization they all serve. All of those charged with positions of responsibility can learn from the example of those who achieve Level 4.0 in this taxonomy and strive towards the same level of accomplishment. |

AuthorBruce M. Mackh, PhD Archives

May 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed