Notice anything?

Here’s the transcript of the ad:

The engineer

And the artist--

They usually live in different worlds,

But when they work together, that’s when you can get something really new,

Something special

Because when great thinkers

Work with great doers

One plus one can equal three.

Since we began, our artists and engineers didn’t set out to make electronics, or films, or music.

We set out to make you feel something.

Now let’s take a look at the subtext of this commercial. If you watch closely, you can see that the engineer is dressed in a blue Sony jacket, while the artist wears regular clothing. In every scene of the commercial, a Sony engineer—indicated by the blue jacket—accompanies someone doing a creative activity—a DJ, a photographer, a camera operator on a movie set—or someone enjoying the arts such as listening to recorded music or playing video games.

In the world of this Sony commercial, the engineer is the thinker, and it is this supremacy of thought over action that drives the creative process forward. The engineer stands by those artists and arts consumers, making their lives better. The artist, on the other hand, seems to disappear from the commercial after the first few moments.

This bias towards thought over action is nothing new to the arts. We’ve been seen by others as mere doers for centuries. Making art was just another form of manual labor until the Renaissance, and in scholarly circles today—where thought is more prized than action—there’s an underlying, but unspoken, belief that artists only make art. Making art is not research, or so they believe. Making art is doing, not thinking.

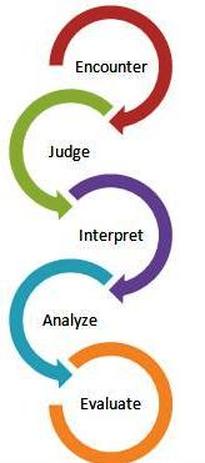

Nothing could be further from the truth. Artists engage in intense ideation throughout the creative process. They are, in fact, high-level thinkers, expressing this thought through the works they bring into being. We might recognize that the work of the artist and the engineer (or chemist, or philosopher, or anthropologist) all depend on being thinkers first, and doers second. We ideate, then we create. The engineer creates new products. The chemist creates new formulas. The philosopher creates new ideas. The anthropologist creates new knowledge about humanity.

If we do not question our underlying assumption that thought precedes action in other scholarly disciplines such as engineering, chemistry, philosophy, or anthropology, why do we discount the arts as being merely doers, not thinkers? Part of the reason lies in the fact that the arts are opaque, whereas the other fields of scholarship are transparent. Scientific discoveries are typically accompanied by hundreds of pages of written documentation explaining the research process that brought the discovery to life. The same is true of humanities or social sciences—each advancement in thought stands upon an explicit investigatory method documented according to scholarly norms.

The arts, on the other hand, deliver no such evidence. Their works appear to have appeared, turning the audience’s whole attention to the product rather than its underlying process. Moreover, scientists receive specific training in practices of documenting their thought process according to rigorous research methodologies. Artists do not.

It is time to recognize that artists are thinkers, not just doers. Part of the path towards this understanding will come through arts-based research, in which artists engage in a meta-cognitive, explanatory process similar to scholars of other disciplines. When we lift the curtain of mystery surrounding our artworks, we allow our peers to see the advanced thinking that makes our doing possible. Because our great thinking—and our great doing—really do add up to something special.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed